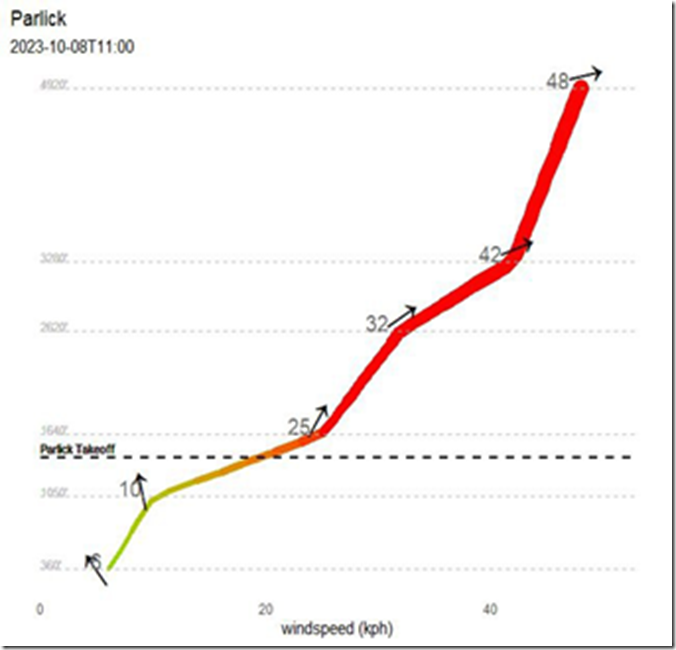

We kicked off the winter club nights at the end of the year with a discussion of the incident on Parlick the previous day. For more information on this see Safety Notes October 2023

John Oliver then gave a talk covering such items as

- Flight preparation using Microsoft Flight Simulator or Condor to get familiar with the terrain before travelling.

- Pictures taken through the season

- What equipment used to take pictures, how to configure the camera and how to post process the pictures captured.

Simon Blake captured some notes below:

1. A suggested minimum spec for a PC to run Microsoft Flight Simulator useably for paragliding purposes would be nice.

Hard drive size: 400GB, It uses a lot!

The scenery is not stored on hard drive, but cached from the internet as needed. So an ok internet speed is needed

A graphics card, GTX1080 ok. I used a GTX1660. Only upgraded to GTX3070 to max out settings with complex 3rd party aircraft (A320 with weather radar and Cu’s reflecting in lakes ect)

Tuning up graphics quality and using 3rd party aircraft increases demand.

20 fps Minimum frames per second required before glitches occur.

2. Details on that sailplane simulator - what's it called, what kit do you need, what's nice to have, what's the Discord server stuff?

Condor 2. Low spec computer ok. Internet only required for multiplayer.

Download from https://www.condorsoaring.com/ 60 euro. And you may end up buying 1 or 4 extra aircraft. Such as a K8 and ASK21 that Boland club fly (To feel how much rudder it requires!)

The multiplayer servers.

https://www.condorsoaring.com/serverlist/?wdt_search=cndr2

Yorkshire gliding club at Sutton bank are the most active uk users.

https://www.condor.club/comp/competitions/202/

The XC league of online soaring. And where the tasks are shown before they appear on the live server list.

Discord is a sever for voice chat used by gamers. Very high quality, no lag sound.

It is also been used as a forum more and more these days.

The UK Virtual soaring club

https://discord.com/channels/647177273232850965/647177273660932145

Yorkshire gliding club at Sutton bank are the most active users.

3. Some recommends on joysticks and other interface devices?

Any joystick ok. Rudder with a twisting joystick or dedicated pedals.

Microsoft sidewinder force feedback 2, USB version form eBay. Made in the 90’s. They don’t make em like that anymore. Not the precision.

Rubber pedels

https://flightsimcontrols.com/product/vkb-sim-t-rudder-pedals-mk-iv-2/

£200 approx. Higher quality than most real aircraft. Pivot style rather than slider, as found in sailplanes.

Head phones and mic.

4. What was that tablet with the colour e-ink screen? Tech specs, manufacturer, purchasing source etc.

I use a TLC S8. Only exported out of China with English operating system by one person on Ali express

https://www.aliexpress.com/item/1005004500210787.html

Sorry, the price has gone upto £510, but he will knock some off if you ask.

Too big for none comp use. RLCD has no back light. Other TLC products claiming to have “NexPaper” are not RLCD

5. What was the app you were using in on for competition? (and what are the alternatives? and do they work on that tablet? (Is it android?))

I use XCTrack. Most comp pilots use it now, plus another device. The task is passed around via a QR code. The XCTrack layout can be very different on a large screen.

6. What was the flight planning app you were using? (Flyxc.app, formerly Thermikxc, if I recall correctly...).

Yep, Fly app.

https://flyxc.app/?s=20&l=ukn

7. I've written "flying with others" - I think there's a whole talk on this but just the recommendation to fly in gaggles.

Yes, defo! Maybe Richard Meek's talk will contain some more on this?

8. What's the name of that woman doing the research about vultures? Where can one find out more about that?

Hanna Williams

https://www.hjwilliams.space/research

Clouldbase mayhem epposide link

https://www.cloudbasemayhem.com/episode-160-soaring-birds-with-hannah-jane-williams/

9. What are the alternatives to Lightroom? (Is GIMP any good for instance?)

Just get lightroom! Everyone uses it.

10. What size monitor do you use, what did it cost etc.?

Ultra wides are made for photo editing. I use a 1440p 34” LG 34UM95. It was £600 years ago and only 60hz. Now there is much more ultra wide choice and they are much cheaper. Unless you want one of the new 4K OLED, HDR, wide gamut, high speed 120hz+ gaming ones!

4k is over kill for a TV at the opposite side of a room. But it is more useful when you are close up to a big monitor. I might need to upgrade. Although don’t get sold on resolution. Like camera mega pixels, The resolution is one of the least import factors, its just easy to sell with. Colour gamut eg 99.7% of RGB or better is more important. Deep blacks, ok dynamic range ect

I calibrated it with a https://www.xrite.com/categories/calibration-profiling/i1display-pro

But my monitor was very close to correct. Just brightness and colour balance where a little off. Sign of a good one. Some bad ones are very far off.

Microsoft Fancy zones

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/powertoys/fancyzones

Good for managing window size on large monitors. As i still view some stuff, like webpages, at 16:9

11. Details of the printing service you use?

https://dscolourlabs.co.uk/

Every one uses them.

Good prices for professional quality

If the print doesn’t turn out how you expect, its your monitor settings that are wrong.

Free test prints too

12. Recommendation for a lens - wide vs. distortion

I’m out of touch. I only know the full frame models. The professional stuff is expensive, but they don’t depreciate. So if you buy / sell a lot, they are cheap after the initial payout. I mostly break even. But the len's don’t break, even if you drop them. Ebay: buy mid-day during the week, sell 7pm on a Sunday.

Google “Flickr lens pool <name of lens>” to see if you like how a lens looks

https://www.flickr.com/groups/14725517@N22/pool

For full geek out read https://www.fredmiranda.com/forum/

13. Recommendation for a body, if you're doing body/lens thing?

As above, i went Sony when they made the first large sensor that was stabilised. Now i know the button layout i stick with them. There is so much choice now. The Sony RX100 used to be the goto good small camera. But also many more options now.

14. Is there a simpler camera that's still a camera that would be usable for flying?

Small is fiddley. I find larger simpler. They all have the same auto functions.

15. Megapixel recommendation - is it always more is better, what do you use etc.

With small sensors, more is normally worse. Apart from smartphones that are using the extra pixels for noise cancelling and to give the AI sharping more to guess with.

Apple proved 12mp was the peak of a phone unless AI was involved.

For a large sensor 12 ok if you dont crop or print large canvas size. Best for low light use, Due to the seize of each pixel.

24pm average these days.

42 over kill. But I like it for deep cropping in. Only the best, mostly modern lens can resolve more than 24mp. So no use without a sharp lens.

Mega pixels is not the measure of how good a camera is. Its just easy to sell with that number, so they are often used in marketing.

To geek out on low megapixel street photography cameras, watch youtube channel:

https://www.youtube.com/@GxAce

16. What are the settings you really need to use in Lightroom and what do they do?

The right hand panel lays its functions out in order of importance. Exposure, white balance and cropping are what are important. The rest is optional.

Import Raw files. And only convert out to jpeg if you need to share.

The evening was well attended and was a great start to the winter evenings!

![clip_image003[11] clip_image003[11]](/media/articulate/open-live-writer-safety-notes-october-2023_f1ad-clip_image003-11-_thumb.png)